TPC Season 1: Secret Sauce

Per my previous post, I have been working my way through The Professional Chef (henceforth referred to as TPC), the Culinary Institute of America’s textbook on the basics of operating a commercial kitchen.

This season, I covered the section on stocks, soups, and sauces, which has meant that my apartment has smelled almost exclusively of simmered onions and butter since January (sorry, Jamie).

Stocks

I’ve been making my own vegetable stocks for quite some time by accumulating and repurposing all the food scraps that come from prepping our meals. I toss onion and carrot tops, celery ends, parsley stems, mushroom butts, etc into a big tupperware container I keep in the freezer. When the box fills up, I transfer the frozen bits to a pot, cover with water, add a few garlic cloves, and simmer for around 45 minutes. After straining, I’ve got a big batch of vegetable stock either to use immediately or freeze for later.

Things I’ve learned:

- Don’t salt the stock–Wait to season until using in a dish, so that you don’t end up with overly salty food. Instead, add vegetables or herbs, or use different cooking techniques (like browning or sweating) to enhance and bring out the complexity of flavor needed.

- Onion skins make the stock turn brown. Not necessarily a bad thing, but to achieve a light-colored broth, remove the skins beforehand. Who knew?

Soups

I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that I have made soup following a recipe over a hundred times in my life, but even so, I also don’t think I ever really thought about the soup-making process. I never considered that there could be a Soup Ratio or Basic Principles of Soup before now.

Things I’ve learned:

-

The fundamental procedure for soup is as follows, but can take on countless modifications depending on your mood:

- Cook vegetables–Start with the ones that take the longest to soften (onions, celery, carrots, parsnips (the mirepoix, if you will) with a generous four-finger pinch of kosher salt and freshly cracked pepper; then add the aromatics (minced ginger, spicy peppers, garlic, lemongrass); and finally add all the others (bell peppers, cabbage, mushrooms, whatever). Cut vegetables to roughly the same size so they cook evenly. Saute until your last additions are about half-done (nobody wants mushy vegetables).

- Add the tomato product, if using–Cook down some tomato paste or sauce to remove some of the acidity and concentrate the tomato flavors, but be careful not to burn. Diced or whole tomatoes (canned or fresh) can be added at this time as well.

- Add spices and dried herbs–Sauteing dry spices helps to develop and deepen the flavors. Be generous and creative. Spices like chili powder, ground cumin, and paprika can be sauteed for about 60 seconds; go with 30 seconds for dried herbs like oregano and thyme since they burn more easily.

- Add stock (or water if you're lazy), as well as any cooked beans, uncooked lentils or grains (rinse those babies before putting them in), potatoes, and anything else that might take about 30 minutes of simmering to cook.

- Simmer for about 30 minutes (didn’t see that one coming), adding more liquid as needed to keep everything submerged.

- Want a chunky soup? Continue to the next step. Want it creamy? Blend that puppy with an immersion blender or transfer to a blender or food processor (make sure to vent the steam as you blend or there will be an explosion).

- Taste and adjust seasonings as required. I didn’t really know what this meant before, so as a guideline, add more salt if it doesn’t taste like anything, more spices if you want it spicier (duh), a sweetener if it’s too acidic, and fresh lime or lemon juice if it’s good but missing something.

- Add any finishing ingredients like fresh spinach, kale, or frozen vegetables, if using. Cook for another 3-5 minutes to warm through.

Sauces

I felt a lot of anxiety about this part of the program. I think it comes from when I watched the movie The Hundred-Foot Journey, which is about an Indian chef who moves to France. He and his family open an Indian restaurant which happens to be right across the street from a posh French eatery, owned by a persnickety woman who thinks all non-French chefs are undeserving posers. In order to become a chef at her establishment, one must audition by preparing each of the Five Mother Sauces of French Cuisine to her liking, which the movie portrays as a nearly insurmountable obstacle for all except the most talented. There’s a happy ending, of course, but for the last decade, I have held onto the belief that these sauces are the pinnacle of one’s cooking game–and I’ve never really been confident that I’d be able to measure up.

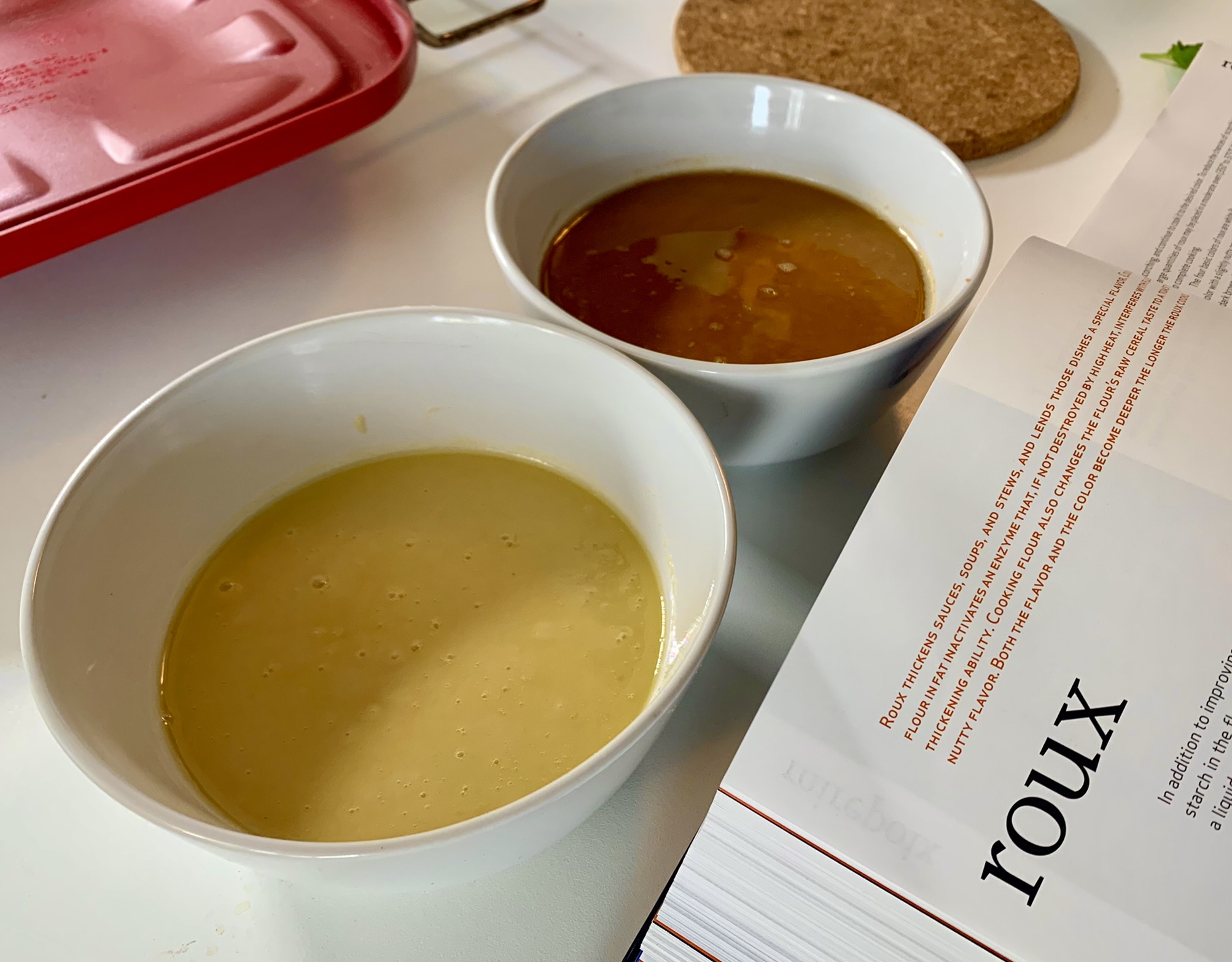

This lack of confidence was validated this past Christmas, when Jamie and I tried to make a roux-thickened sauce as part of our dinner. Roux is a mixture of flour and fat. When you cook flour in the right amount of fat, some of the thickening power of the flour gets softened and you’re supposed to be left with a smooth, stable, and creamy sauce/gravy. When you cook flour in the wrong amount of fat, you end up with a slightly thickened liquid speckled with a bunch of teeny tiny dumplings. Seeing, then, that the first section of TPC pertained to sauces had me feeling a little uneasy (and a little bit attacked).

The Five Mother Sauces

- Bechamel – Light roux + milk

- Velouté – Light roux + white stock

- Espagnole – Brown roux + brown stock

- Tomato – Roux + tomatoes (or skip the roux and thicken by simmering)

- Hollandaise – Egg yolks + acid + melted butter

Even though I cook vegan at home, I decided to try these sauces using the traditional, non-vegan ingredients. For the first time in something like 7 years, I purchased milk, butter, and eggs like some regular person. I narrowly avoided the Vegan Police on my way home, but every knock on the door and bump in the hallway still puts me on edge.

Over the course of the last few months, I’ve made each of these sauces for varying purposes (except velouté, because I cannot be bothered to peel my onions before making stock), and it culminated with a 48-hour cooking marathon for a super fun dinner party where we ate too much and watched the Reel Rock 16 premier (AKA my midterm exam).

Bechamel

Espagnole

Tomato

Hollandaise

Things I’ve learned:

- Sauces can be thickened with a roux or with a starch slurry (mixture of water/stock and cornstarch, tapioca flour, etc).

-

- Roux can have a variety of flavors depending on how long it cooks, and can give a lot of complexity to a sauce. White roux tastes creamy and mild; brown roux tastes very nutty, almost like buttered popcorn.

- Roux holds up well to high heat and to reheating, and takes about 20-30 minutes of simmering to cook out the floury taste.

- Roux can be stored indefinitely in the fridge or freezer. Heat it up before adding to a sauce to avoid drastic temperature changes.

- Starch slurries thicken sauces very quickly and are good for finishing. They leave a super glossy sheen but their thickening powers can break down upon reheating.

- I broke my hollandaise sauce on Exam Day by letting it get too hot while I was preparing another part of the meal. Turns out, you can fix it by slowly whisking the broken sauce into another beaten egg yolk. It’s actually witchcraft. Would recommend, if only to see the magic happen.

- Tomatoes get more concentrated as they simmer, but turn a little bitter after about 35 minutes. It is not tomato season, so I can’t say what using fresh tomatoes is like, but I found I liked using canned whole tomatoes over any other canned tomato product.

- I will eat espagnole sauce over anything. It’s that good.

And that concludes Season One of The Professional Chef. Honestly, I think The Hundred-Foot Journey was a bit dramatic. The sauces do take attention (admittedly, a lot), but they're not that difficult. Really, it's mostly a lot of whisking (like, I was getting kind of pumped, but that might also be because I'm working with a toddler-sized whisk). I doubt that I’ll make hollandaise or bechamel very often, but it feels good to have learned these skills, and I’m pretty sure Christmas Dinner: The Sequel would be infinitely better than the original.

Next season will deal with “Vegetables, Potatoes, Grains & Legumes, and Pasta & Dumplings” (basically everything), and I’m looking forward to learning how to better prepare the bulk of my diet. Until then!